Please review our new editorial policy

Some pretty powerful things happened when I completed the Destroy All Starships series. Anticipation was high for the next adventure, and still is. There are a lot of unresolved plot threads that were established in previous books going all the way back to the first novels in Starships at War. In particular, readers were invested in the outcome of the Ithis Technology arc, and the whereabouts of the Denominator. You’ll be pleased to learn those subplots have been quietly building alongside the alarmist/anti-alarmist conflict in the human military and government. Part of the growing conflict reached a breaking point just before the pivotal meeting between President Baines and Admiral Powers.

Some of the subplots I’ve been weaving behind the events of Hunter Killer and Operation Justicar re-emerged in The Infamous 24 and early chapters of Last Charge of the Defiant. I have a number of new works in development, and I’m looking forward to sharing them with you all very soon.

In the meantime, my “current projects list” can be summarized as follows:

Advanced Starship Tactics Series

I am just over 11,000 words into this novella. It is the first book in a new trilogy. It will detail the confrontation set to take place at the doorway to the Atlantis sector, where an unexpected wreck was discovered, and the crew of DSS Sai Lore is about to find themselves at the center of one of the most intense deep space battles in the entire series!

I am just over 7,000 words into this new and refreshing story. It’s science fiction, not necessarily military (even though the protagonist is a decorated U.S. Army officer). It is a story that will very likely be meaningful to a number of men, many of whom find themselves isolated and besieged by circumstance, intentional or otherwise. Ai also explores what it would be like if technology was on our side for a change. It is currently a Bitbook exclusive.

Destroy All Starships Series

As part of my ongoing project to release all of the titles on my backlist as affordable (and signed) trade paperback editions, I recently updated the #1 New Release that launched both the Siege Island and Destroy All Starships series complete with a brand new limited edition cover. I am currently working on the paperbacks for all my “firsts” including Strike Battleship Argent and Battle Force.

Let None Return Alive is on sale (25% off) now.

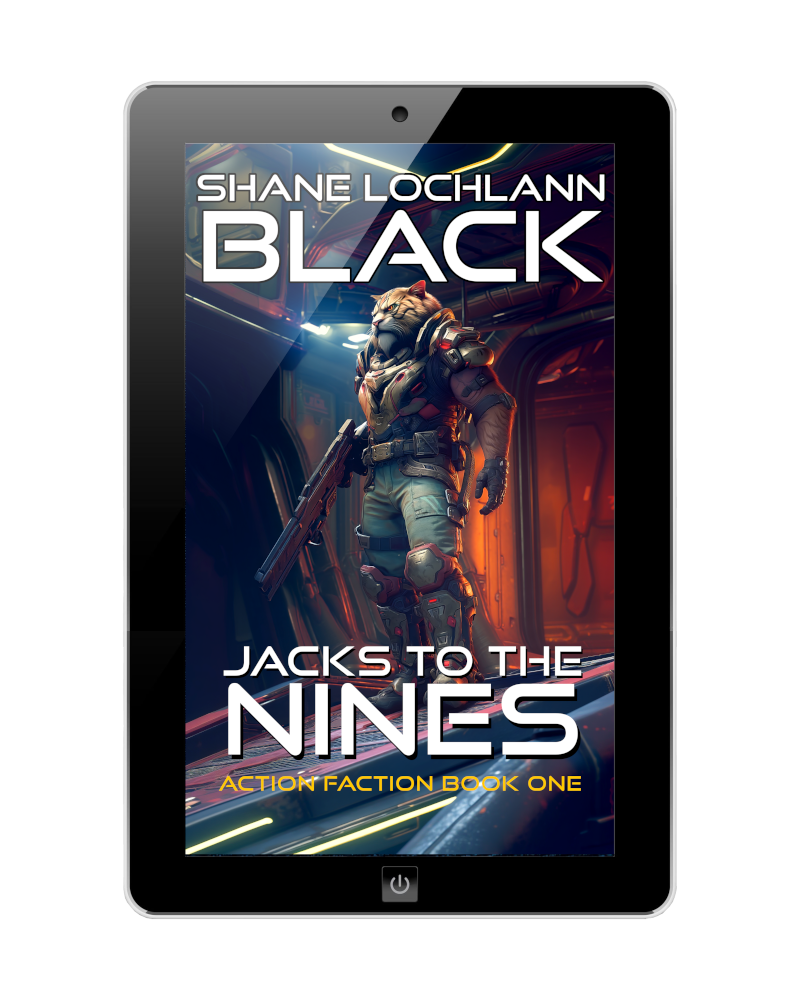

Action Faction

I am just over 10,000 words into this novella. It is an exclusive I’m writing for our most supportive reader from my Action Faction project, where I offer a completely unique custom book written for an audience of one. Jacks to the Nines is the story of an attack by a combined Human/Proximan task force against a hidden forward Sarn base discovered in the Platmore system. The Bandit Jacks even take to their fighters to perform a direct strike against the defenses constructed on Racer’s Moon just before they invade the sublevels and discover something nobody could have possibly expected. Features appearances by Lord-Captain Oakshotte and none other than Gurguul the Butcher!

Build a Starship Campaign

It goes without saying stories like the ones I write should include numerous futuristic technology concepts, especially as they relate to space exploration, military hardware, resource development, autonomous mechanisms and energy production. But this is the first time I’ve contemplated a book that is nothing but futuristic technology! If you have ever wondered what it would be like to explore the battleship Argent deck by deck and cabin by cabin, this title should definitely be on your list. The technical manual is the foundation reward for the Build a Starship campaign, and I’ll be making some preview available as part of our crowdfunding project very soon.

Next up we’ll get you up to speed on our campaign to construct a real (model) spacecraft you can proudly display on your bookshelf at the office or at home!